While recent advances in processing power, miniaturisation and battery life

have transformed most mobile electronics, one aspect of them has hardly changed.

We still tolerate cramped PDA displays, laptop monitors that work only if you’re

looking directly at them and mobile phone screens that are barely visible in sunlight.

But a brighter future may finally be at hand, with new active matrix OLED displays

that outclass traditional LCD screens in almost every way.

The LCD market is certainly one worth gunning for. This year, over 500 million

LCDs will be fitted to mobile phones alone and, with the growth of photo messaging

and 3G (third generation) services worldwide, nearly half of those will be full-colour

displays. Manufacturers are relying on our hunger for ever more comprehensive

mobile services to shift a new generation of PDAs and full-motion videophones,

and Kodak hopes that its OLED displays will poach over $3 billion of LCD business

by 2005.

The latest organic light emitting diode (OLED) displays offer vivid images and

crisp video without the use of a backlight, and are therefore thinner, lighter

and use less power than conventional LCDs. Patrik Bluhme, Marketing Director of

Kodak Digital, explains: “The major advantage of OLED is its low power consumption.

In an LCD the backlight is always on, whereas every OLED pixel is like a dimmer

switch; rarely turned off but very rarely turned fully on.” OLED screens

also have refresh rates up to 1000 times that of LCDs, making them ideal for showing

video on camcorders, PCs and even televisions. A wider viewing angle of up to

165 degrees means that screens are still fully visible from almost side on and

OLEDs also boast superior contrast and colour reproduction. But the best thing

about OLEDs is that they’re available right now.

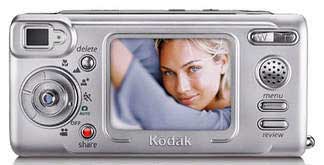

This April, Kodak is launching the world’s first consumer product with an

active matrix colour OLED display, the LS633 digital camera. Digital photography

is currently witnessing a frenzy of technological one-upmanship similar to the

one that fuelled the mobile phone explosion of the late ’90s. Up until now,

much of the innovation has been based around increased image resolution, with

built-in screens remaining small, heavy and power hungry.

The LS633 is set to change that single-handedly, with a 2.2-inch OLED display

that has over twice the viewing area of most rivals’, while drawing significantly

less power. But it’s the wide-angle viewing possibilities that Kodak thinks

will drive sales. “Our consumer research shows that the wow-factor with

digital photography is not when the picture is being taken but afterwards, when

everyone gathers round to see the result,” says Bluhme. “Everyone

wants to see the image – and with an OLED display they can all do it at

the same time, indoors or outdoors.”

The concept of OLEDs has been around for a few years and passive (largely monochrome)

displays are already in the marketplace. Kodak is the first company to develop

a full-colour, full-motion active display that’s both cheap and reliable

enough for the consumer market. The fundamental difference between OLEDs and LCDs

is that LCDs are transmissive displays, forming images by blocking light from

a reflective surface or light source mounted behind the array. By contrast, OLEDs

are emissive, with the material itself producing light through a process known

as electroluminescence. This eliminates the need for a heavy and often eco-hostile

mercury backlight.

An OLED display consists of a stack of thin organic films sandwiched between two

conductors. When a few volts are applied to the cell, injected positive and negative

charges recombine in the organic polymer to produce light. Each of the organic

layers is just a few hundred nanometres thick (that’s thinner than the wavelength

of green light) and their precise composition is a closely-guarded Kodak secret.

But creating light is only half the battle. In order to reproduce full-motion

colour images, OLEDs need thin-film transistors (TFTs) similar to those used in

active LCD screens. The result is a display in which each individual pixel can

be set to an exact brightness, and that isn’t limited by pixel count, size

or resolution. OLED displays are better than LCDs even when they go wrong, with

pixels failing ‘dark’ instead of the noticeable bright point defects

seen on damaged screens today.

Although its power- and weight-saving features make OLED technology most attractive

to mobile users, the improvements in colour reproduction, viewing angle and responsiveness

mean that the lucrative laptop and large screen TV markets are longer term goals.

Kodak showcased a 15-inch monitor at this year’s CeBIT show and an IBM joint

research venture has already produced a 20-inch OLED prototype.

With an estimated market of $30 billion for large screen TVs in 2006, it’s

hardly surprising that today’s technologies are refusing to join Betamax

video and 5¼-inch floppy discs in the museum just yet. Plasma screens are

cheaper than ever, with 42-inch models now retailing beneath the magic £2,000

barrier. And although LCD technology is getting long in the tooth, increasingly

large scale manufacture is driving prices ever downward. “OLEDs will coexist

with LCDs rather than replace them,” according to Kodak’s Patrik Bluhme.

“LCDs benefit from a variety of active and passive technologies, and there’s

still some way to go with hybrid transflective displays.”

Even the old cathode ray tube is set for a high-tech renaissance, with the development

of super-thin sophisticated printable field emitter displays (FEDs). These comprise

a series of self-assembling nanophase inks, dubbed ‘magic ink’, that

can printed on to a glass substrate to create electron-emitting sites. When voltage

is applied, these sites fire electrons into a phosphor screen to form images in

the same way as a traditional TV, albeit without the bulky glass tube.

But even as the first OLED products screens hit the shelves, researchers are working

on next generation systems that combine the new technology with advances in materials

science. The Universal Display Corporation has operational transparent OLED (TOLED)

displays that are up to 70% transparent when turned off, raising the possibility

of smart windscreens with heads-up GPS navigation, TV-equipped specs or even windows

where you can choose the view.

Stretching the acronym even further are FOLEDs, folding OLEDs that can be made

on materials ranging from flexible textiles to reflective metal foils. Roll-up

electronic newspapers and chameleon-style adaptive clothing are two of the more

esoteric products promised for the medium term.

Such sci-fi concepts aren’t limited to high-tech labs. Researchers at the

University of Tucson have succeeded in creating a simple OLED display using an

everyday consumer inkjet printer. Inkjet printers direct bursts of ink as small

as a few picolitres to within an accuracy of 25 microns. Replace the inks with

the correct organic polymers and your home printer can be programmed to output

complete OLED structures. Need a new screen for your PDA? Just print one out!

In the meantime, Kodak is already licensing OLED technology to a dozen display

and device manufacturers around the world. More OLED cameras, phones and PDAs

will arrive very soon, with high-end laptops hot on their heels. And if the quality

of Kodak’s first screen is anything to go by, the future for OLED displays

looks very bright indeed.

Click here

to view this feature on The Independent's website